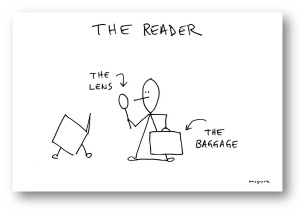

Thanks to Dr Kate Murphy of Oriel for this func -y metaphor for competent literary text investigation which I have used with success on all students from the 6th Form down (heavily paraphrased, but in essence this is what she said):

‘When reading a text, you have to imagine you are piloting a submarine deep under the sea. And when a light flashes on the dashboard, that’s worth taking note of, but not in and of itself – it is a signal to you that something needs investigating. The noticeable light is telling you to keep on looking out there, to reach out and grab whatever set the sensor off and then to study that thing lurking out there in the deep more closely. Or it is telling you that something is going on in your submarine and you need to get out your tools and work out what’s occurring inside your engine. Students coming up from 6th Form often spot techniques at work in texts and treat them as the end in itself – ‘oh look, an extended metaphor’ – without following up to delve deeper and discover what your sensor is alerting you to in the ocean of meaning of the text. I would prefer it if students spotted the technique light on the dashboard of the poem and then really went after the reason for its existence.’

Thank you Dr Murphy: http://www.english.ox.ac.uk/about-faculty/faculty-members/early-modern/murphy-dr-kathryn

Students need practice doing this, even if they find the unknown scary (which of course, due to the action of the amygdala, they always do – read more on that here: http://www.risk-within-reason.com/2011/12/06/girls-thrive-deak/ ), so we need to find ways to:

a) make this fun,

b) show them it can be done,

c) leave them to struggle with doing it for a bit,

d) provide them with the right tools to use so that they can do it themselves,

e) let them know – and then make sure – that we will mark with attention to the meaning they produce. Null points for empty points or mere feature spotting.

RESOURCE ALERT! RESOURCE ALERT! RESOURCE ALERT! RESOURCE ALERT!

RESOURCE 1: It goes without saying that simply lists of definitions tested for reproduction of those definitions won’t do it. So here is a list I made of the tools they need, in Quizlet form, for learning and then / at the same time applying: http://quizlet.com/71907710/flashcards

RESOURCE 2: I heartily recommend also the glossary and marking guide at the back of this simply fantastic book on essay writing, http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-EHEP003057.html which actually does recognise the real world and real purpose of the literary analysis essay as practiced at the Universities at which I am interested in my students being able to work competently once there.

If students realise the depth of meaning and personal satisfaction they can gain from the adventure of genuine literary text investigation, it will carry them a very long way. We need to communicate to them that this is what real literary critics do and what therefore they would be expected to do in the next phase of their literary critic apprenticeship at University (see my earlier post on Doing Difficult Things for the importance of a shared goal and communicating the values that go with it to all involved according to the theories of Lave and Wenger about building successful Communities of Practice).

In personality focus, or mental adaptation, or role-playing, perhaps they need to become a mixture of all four main characters from Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: the admirable servant Conseil who can name and classify everything in the sea, but stops there; his master, Professor Arronax who knows the science and is sufficiently excited by discovery to almost want to stay on board the Nautilus in spite of his isolation, but represents also the need to share knowledge; Ned the Whaler who knows about the sea and its beasts in practice, representing the intuition built of long-time grappling with the environment at hand; and Captain Nemo, who has become to attached to the realm of the sea that he refuses entirely to leave it. We don’t want to make Captain Nemos, so isolated in their study that they don’t think about the human impact of texts, nor do we want our students harpooning the texts to death in a cowboy of the sea fashion, but a mix of these approaches would do the trick.

Analyse this for connotation and form! – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vefJAtG-ZKI

Do not tell your students about this – http://www.kongregate.com/submarine-games

Dr Murphy gave me this cracker a couple of years ago answering a questionnaire from me about what University English departments want students to bring with them in terms of what they are able to do when they arrive, particularly in the realm of essay writing. I was not very covertly seeking to test the relationship between the WJEC’s A-level Assessment Objectives and the real life of academic literary criticism.

In short? Universities want a functional approach to the study of literature, whatever their bias is. They know that authors use words to do stuff and they want students to think this way.

- Oxford – wanted AO2 to be properly meaningful and prompt investigations of texts, with a sense of the meaning of texts being linguistically constructed as well as socially.

- Kings – wanted AO4 to be properly meaningful and use a wide range of historical parallel sources. Keen on comparative reading across genres, within periods.

- UCL – keen on comparative reading AO3.

- All – wanted students to read for themselves, making a sensible stab at interpreting the ideas and issues raised by a text in AO1 stylee before resorting to AO3 critique. All also wanted critical ideas to be read, summarised and debated, not used as (gobbets or just gob).

Result? Pretty darn good work on the part of WJEC, with varying biases depending on which institution you ask. This is good as the AOs are remaining virtually unchanged with the reforms coming into place this year. Some acknowledgement that it is a bit strange to apparently champion Cambridge- style Practical Criticism with attention to the words of the text itself taking primacy in AO1 and AO2, whilst at the same time including contextual/biographical/historiographical (is that even a word?!) reading in AO4. And if you are a textual Deconstructivist like me, (beware my volumes of Helen Vendler coming at you in sonnet lessons), but with an obsession with understanding where any of this came from, then you basically just teach entirely AO4 period and genre awareness with AO2 analysis as the meat of any text work. But whatever we do, it has to be the students who are able to do it.